|

GUARDIAN

& INDEPENDENT, Jan-March 2016

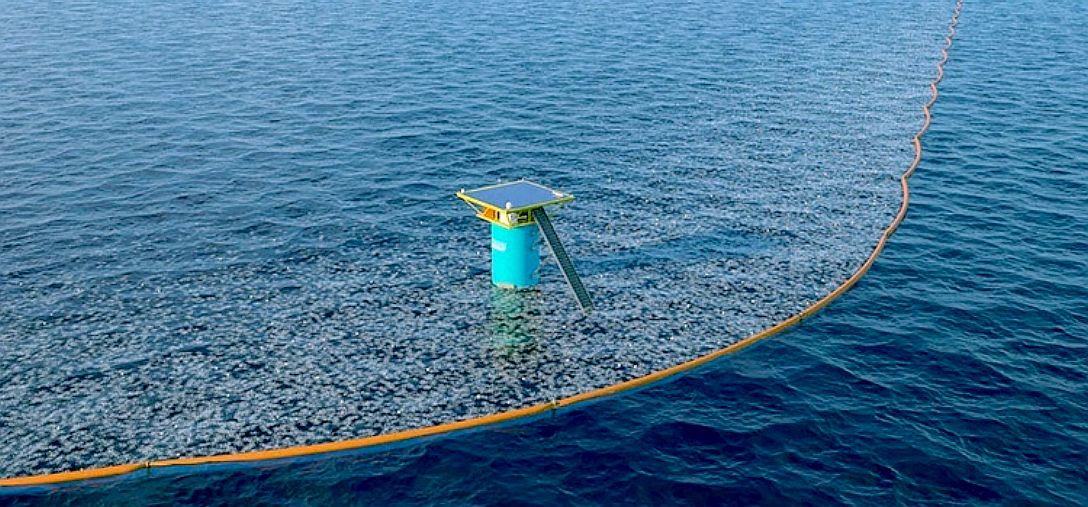

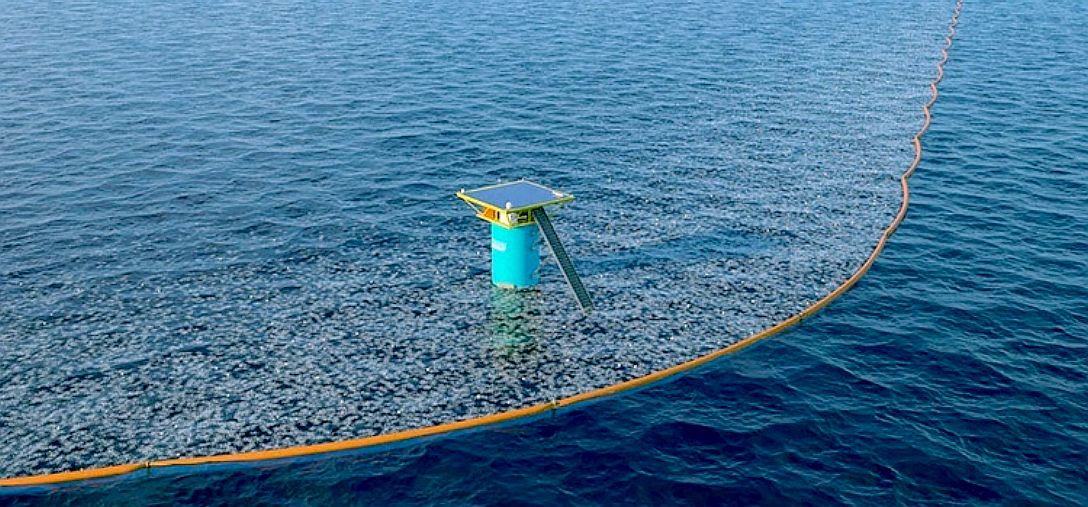

DELFT

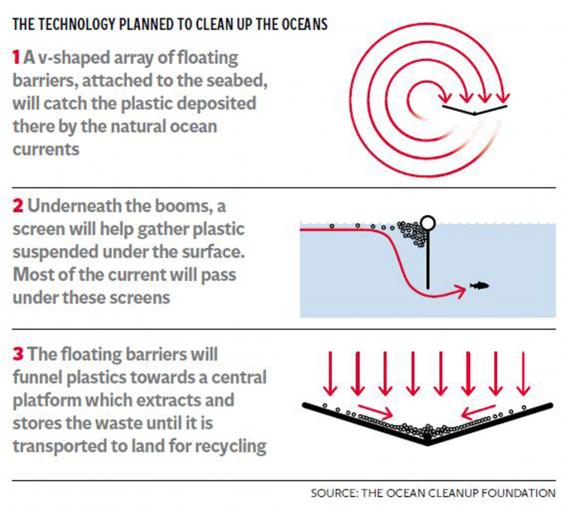

UNIVERSITY - This is an artists impression of what the

ocean boom might look like, given that the design has not yet

been finalized.

Scientists and volunteers

gathering data on how much plastic garbage is floating in the Pacific Ocean returned to San Francisco on Sunday and said most of the trash they found is in medium to large-sized pieces, as opposed to tiny ones.

Volunteer crews on 30 boats have been measuring the size and mapping the location of tons of plastic waste floating between the west coast and Hawaii that according to some estimates covers an area twice the size of Texas.

THE INDEPENDENT - JANUARY 19 2016

- HOW SCIENTISTS PLAN TO CLEAN UP PLASTIC WASTE THREATENING MARINE LIFE

It is estimated that about eight million tons of plastic debris are being washed into the oceans each year.

Scientists have worked out the best way of removing the millions of tons of plastic waste floating in the oceans – a time bomb that threatens to poison the marine ecosystem.

It is estimated that about eight million tons of plastic debris such as food packaging and plastic bottles are being washed into the oceans each year, where it is broken down into smaller “microplastics” that act as a magnet for chemical toxins ingested by the smallest sea creatures.

The cumulative amount of plastic in the ocean is set to increase tenfold by 2020, with the consequences extending centuries into the future because of the length of time it takes for plastics to biodegrade – resulting in calls for a global initiative to collect plastic waste floating on the sea surface.

There is already an ambitious, crowdfunded plan to gather plastic waste circulating in a huge “garbage patch” in the middle of the Pacific Ocean using 100km-long, inflatable booms aligned across sea currents. But a new study suggests that this will be far more effective if carried out near densely-populated coastlines, especially off China and Indonesia, where much of the waste enters the sea.

The so-called Great Pacific garbage patch is a highly visible illustration of the scale of the global problem. However, the researchers believe it would be better to tackle the clean-up nearer to its source on land, where an equivalent of five grocery bags of plastic is being dumped each year on every foot of coastline in the world, say scientists.

The study, carried out by a team at Imperial College London, compared two hypothetical methods of collecting marine plastic over a 10-year period between 2015 and 2025 – either by skimming the waste from the middle of the ocean or by positioning the collecting booms just off the coast near densely-populated areas.

Computer modelling suggested that placing collecting devices nearer the coasts would remove about 31 per cent of microplastics – the smaller plastic chips and fibres that result from the environmental breakdown of larger items.

However, when all the collecting booms are placed inside the circulating, mid-ocean garbage patches, only 17 per cent of microplastics would be removed, according to the study published in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

“It makes sense to remove plastics where they first enter the ocean around dense coastal economic and population centres. It also means you can remove the plastics before they have had a chance to do any harm. Plastics in the patch have travelled a long way and potentially already done a lot of harm,” said Erik van Sebille of Imperial College, who led the work.

Although there is a huge mass of plastic waste circulating in the the ocean “gyres” – circular ocean currents – it would be more efficient to tackle the problem from where most of the waste enters the sea in the first place, which coincidentally is richer in marine wildlife, said Peter Sherman, an undergraduate physics student involved with the study.

“The Great Pacific garbage patch has a huge mass of microplastics, but the largest flow of plastics is actually off the coasts, where it enters the oceans. There is a lot of plastic in the patch, but it’s a relative dead zone for life compared with the richness around the coasts,” Mr Sherman said. “We need to clean up ocean plastics, and ultimately this should be achieved by stopping the source of pollution. However, this will not happen overnight, so a temporary solution is needed, and clean-up projects could be it, if they are done well.”

A study last year of 192 countries found that most of the plastic waste in the oceans comes from people living within 50km of the coastline. It estimated that 275 million tons of plastic waste is generated each year around the world and between 4.8 million and 12.7 million tons ends up either being washed or dumped deliberately into the sea.

Another analysis found that 90 per cent of seabirds have swallowed plastics and that these birds are concentrated around coastlines.

Predictions of how the quantity of plastic waste will increase took into account the growing industrialisation of developing countries, population growth and attempts to limit the flow of plastic debris into the oceans based on waste-management activities on land.

By Steve Connor (science editor)

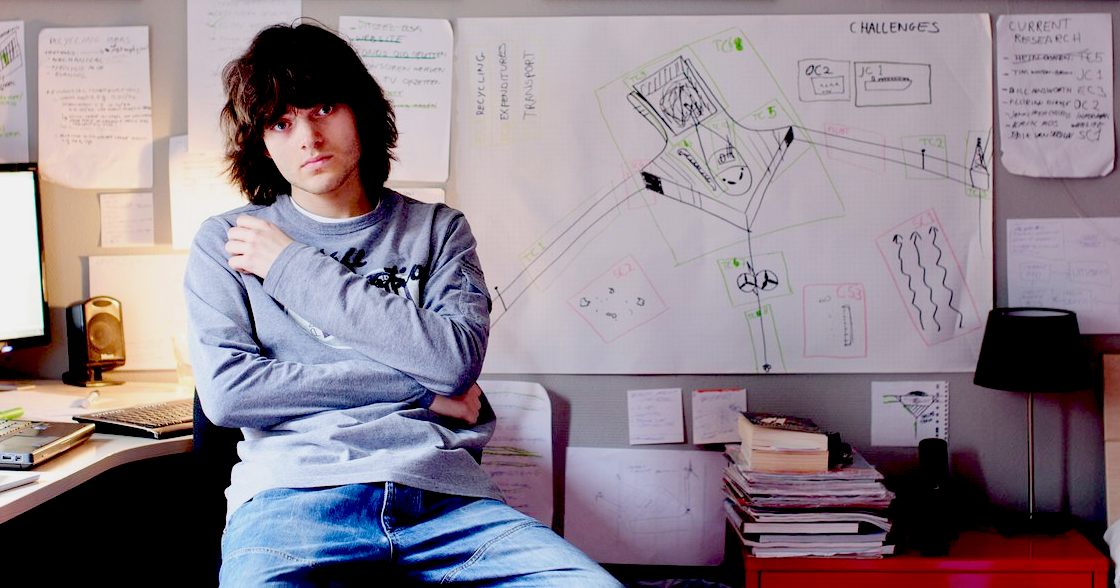

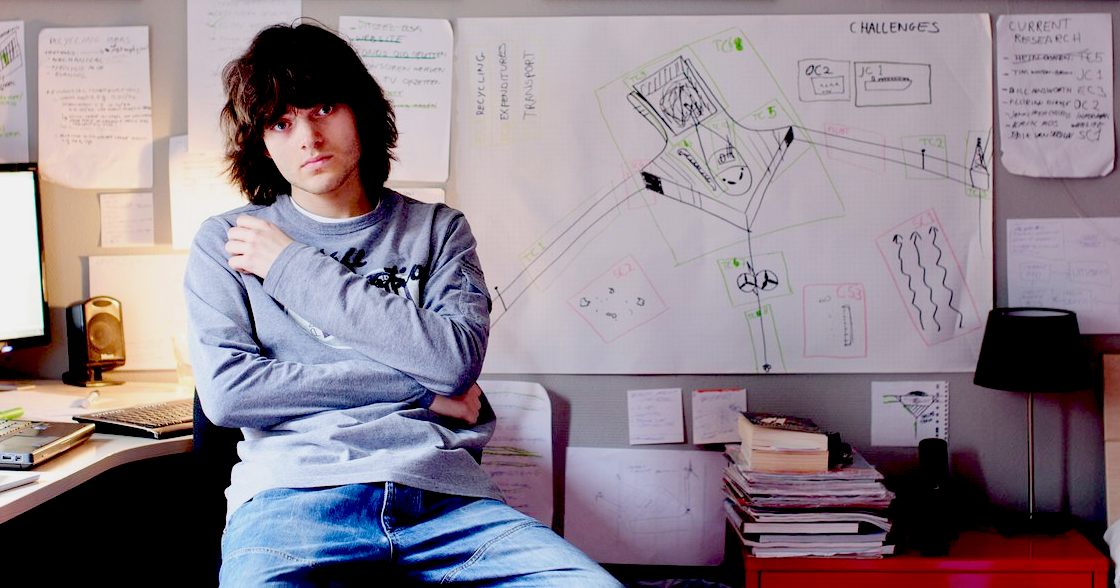

BOYAN

SLAT

- The originator of the ocean boom concept in his study

SEABIRDS

- Are extremely vulnerable because they are attracted to

brightly coloured floating objects, thinking it is a meal,

when in reality the bottle tops are a man made deception.

THE GUARDIAN - TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE

THE OCEAN CLEANUP PROJECT FACES FEASIBILITY QUESTIONS 26 MARCH 2016

Last year, nonprofit foundation The Ocean Cleanup hit a milestone en route to its goal of deploying a large, floating structure to pull plastic from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The organization issued a press release announcing it had completed a reconnaissance expedition that would pave the way for a June 2016 test of its prototype. With the help of $2.2m in crowdfunding, 21-year-old founder Boyan Slat announced his plans to deploy 100 kilometers of passive floating barriers in an effort to clean up 42% of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch’s plastic pollution in 10 years.

Despite considerable online enthusiasm for the project, oceanographers and biologists are voicing less-publicized concerns. They question whether the design will work as described and survive the natural forces of the open ocean, how it will affect sea life, and whether this is actually the best way to tackle the problem of ocean plastic – or merely a distraction from the bigger problem of pollution prevention. Many have also expressed concern about the lack of an environmental impact statement prior to such a large push for funding.

“The thing is, what we’re trying to achieve has never been done before,” Slat says. It’s 100 times bigger than anything that’s ever been deployed in the ocean. It’s 50% deeper, and 10 times more remote than the world’s most remote oil rig. So obviously there [are] technical challenges.”

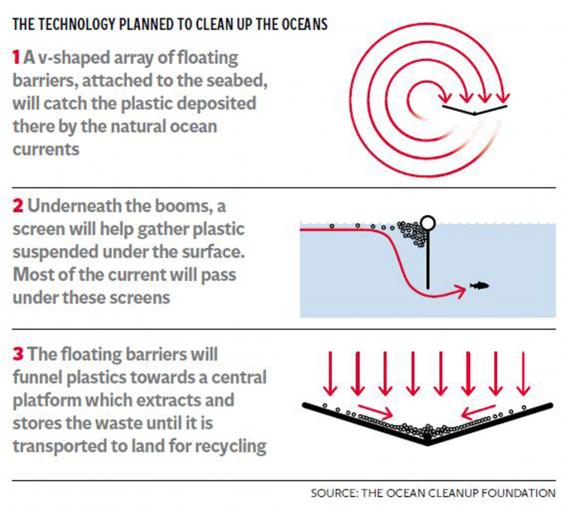

In the summer of 2014, The Ocean Cleanup released a 528-page feasibility study, which Slat and his team used to determine that the project was possible. As described in the study, the passive system relies on wind, waves and currents to push the floating plastic into screens that extend from the floating barriers like a skirt. The idea is that the current can pass beneath the screens, which will prevent bycatch of plants and animals. Since

plastic floats, ocean pollution between 35-100 millimeters in size will be captured by the barriers. The v-shape of the array then concentrates the plastic pieces at the center of the structure, where they can be harvested and then sorted and processed in a collection platform. After the plastic is processed, it will be collected by boat every six weeks, with the hope that it can be sold as recycled material.

In the feasibility study, The Ocean Cleanup offers four possible designs, but Slat says they’re still working on finalizing a concrete design of the collection platform.

Scientists like physical oceanographer Kim Martini and biological oceanographer Miriam Goldstein still aren’t convinced that the structure can overcome the technical challenges. After the feasibility study was published in 2014, Martini and Goldstein published their own technical review on DeepSeaNews.com. They say their concerns have remained largely unaddressed.

Martini says Slat’s response was limited to a statement he made on a discussion panel. While he said he was “very happy they have read it”, and that they made valid points, Martini doesn’t think Slat has made a sufficient response to his concerns.

“We continue to have serious reservations about the success of the project due to the quality of the responses [to our review] that we could find, and [to] the Ocean Cleanup’s substantive misinterpretation of oceanography, ecology, engineering and marine debris distribution, all of which are necessary for this project to succeed,” Martini wrote in an email.

LULU

THE ORCA

- Found dead on the island of Tiree, Lulu is thought to have died an excruciating death after becoming entangled in fishing rope.

At the moment, the only project that is looking to extract

ropes and nets from the oceans is Operation SeaNet, using

SeaVax robotic ships.

MINKE

WHALE BEACHING

- Killer whales and dolphins are facing the threat of extinction in UK waters because of lingering toxic chemicals which were banned more than 30 years ago, researchers have warned.

A study of more than 1,000 whales, dolphins and porpoises across Europe found their blubber contained some of the planet's highest concentrations of a man-made chemical known as PCB.

PCBs - or polychlorinated biphenyls - were previously used to make electrical equipment, flame retardants and paints but were banned in the UK in 1981.

The study's lead author Dr Paul Jepson, from the Zoological Society of London (ZSL), said killer whales and bottlenose dolphins were particularly vulnerable to the pollutant as "top marine predators".

He said: "Our findings show that, despite the ban and initial decline in environmental contamination, PCBs still persist at dangerously high levels in European cetaceans.

"Few coastal orca populations remain in western European waters. Those that do persist are very small and suffering low or zero rates of reproduction.

"The risk of extinction therefore appears high for these discrete and highly contaminated populations. Without further measures, these chemicals will continue to suppress populations of orcas and other dolphin species for many decades to come."

Experts found killer whales, bottlenose dolphins and striped dolphins had the highest concentrations of PCB in their blubber.

High exposure to the chemical is known to weaken their immune systems and markedly reduce breeding success by causing abortions or high mortality in newborn calves, researchers said.

The study, published in the Scientific Reports journal, identified the western Mediterranean Sea and south-west Iberian Peninsula as having the highest concentrations of PCB in Europe.

The report's co-author Robin Law said: "Our research underlines the critical need for global policymakers to act quickly and decisively to tackle the lingering toxic legacy of PCBs, before it's too late for some of our most iconic and important marine predators.

"We also need to better understand the various pathways through which these iconic species are able to accumulate such high PCB concentrations through their diets."

The UK Cetacean Strandings Investigation Programme (CSIP) was set up in 1990 to investigate whales, dolphins and porpoises that strand around the UK coastline, as well as any marine turtles and basking

sharks.

Since the feasibility study, The Ocean Cleanup team has focused the most on the engineering and design side, according to Slat. Since 2014, Slat and his team have deployed two scale model tests at water research centers called Deltares and Marin. Based on the scale tests, the team is trying to better understand and model how the structure will react to the wind, waves and currents it will experience in the open ocean, and how plastic will behave. Slat is characteristically optimistic. Though Martini and Goldstein wrote that the feasibility study underestimated the forces of currents and waves, Slat says based on his tests, “the forces are actually a lot lower than we thought they would be”.

Another force the array might have to contend with is biofouling. Biofouling happens when marine life affixes itself to the structure, weighing it down and affecting its performance. Nonetheless, Slat does not see this as a concern. “We’re testing different environmentally friendly coatings to prevent biofouling,” he says. “It’s something that is an active part of our research, but it’s not on our top 10 list of concerns.”

While the feasibility study devotes pages to the impacts on phytoplankton and zooplankton and other sea life, it fails to consider species that actually live in the gyre region, according to critics. In a September 2015 blog post, 5 Gyres, an activism, research and education nonprofit dedicated to issues of aquatic plastic pollution, pointed out that buoyant organisms like Velella velella or purple janthina snails that float along on the surface would likely not be able to flow beneath the array’s screen as planned. “The potential for ‘bycatch’ is too great to be ignored,” 5 Gyres writes.

“It’s unfortunate that there were some taxa that were covered that aren’t in the gyre,” Slat says, citing the large number of volunteers who worked on the study. “But we don’t want to create new problems. Right now we don’t see any evidence based arguments why it should be a problem.”

The Ocean Cleanup’s array, as deep-sea biologist Andrew David Thaler wrote on SouthernFriedScience.com, is also a fish aggregating device. As the v-shape concentrates plastic debris in the center, it also has the potential to attract predator and prey species, disrupting their normal behavior or migration patterns. It could also make them more susceptible to consuming the plastic accumulating in the array.

The Ocean Cleanup is continuing to test and refine the concept. After the crowdfunding campaign in 2014, Slat hired 35 more employees “to really get some speed and tackle these challenges”.

The team has done a series of six expeditions since 2013 to measure the depth and size of ocean plastics within the gyre, the results of which will be published in a study that Slat says he “will be submitting to a high-impact open-access peer reviewed journal”.

The next step he plans to take with his team is to deploy a prototype in the North Sea this summer. A 100-meter segment – or about 1/1000th of the planned array – will be set up about 20 kilometers off shore.

Slat says The Ocean Cleanup prepared for this next phase of testing by conducting an environmental impact analysis with Royal HaskoningDHV.

Then, early next year, the team plans to deploy a pilot off the coast of the Japanese island Tsushima, in the Korea Strait. Slat says he chose the location because of the large quantities of accumulated plastic due to ocean currents.

But even after these technical studies, there will still be lot of uncertainties. The rope mooring systems cannot be properly tested off Tsushima, for example, because the depth doesn’t match that of the open ocean. And Slat admits that deploying something out in the middle of the ocean will be expensive to fix if something goes wrong.

When it comes down to it, it could be that the biggest problem with the project is focusing on the gyre itself.

“We generally applaud the motivation and energy of The Ocean Cleanup to tackle this problem,” says SEA Education Association research professor Kara Lavender Law. “[But] it’s more efficient to trap plastic as it’s coming away from its source rather than dispersed across large areas.”

Even if the gyre cleanup were viable, says Law, it would be like “mopping up the bathroom floor without turning off the faucet to the tub”. Humans will continue to dump about 19bn pounds of plastic into the ocean each year. And as the larger pieces of plastic travel, they break down into microplastics that sink to the ocean floor and are much more difficult to clean up.

Climate scientist and oceanographer Erik van Sebille has found that it can take up to 50 years to reach the garbage patches: “That means that even if we would clean up the garbage patches today, the garbage would return within a few decades, as the plastic that is currently spread across the ocean slowly accumulates again,” he wrote.

Slat is undeterred, however. “The ocean garbage patches won’t disappear by themselves,” he says. “If you collect plastic closer to the source, the total mass that you remove may be larger, and the influx to the gyres would be reduced. Our focus however is on the necessary task of removing the plastic that already reached the gyres.”

While it doesn’t have the same appeal as a giant passive structure that can help the ocean clean itself of plastic, Law notes that beach cleanups that get people to tidy up their own shores, like the International Coastal Cleanup, do make a difference. In 2014, the initiative collected more than 16m pounds of trash.

By Lindsey Kratochwill

IT'S

NOT SPORTING

- Just like the situation at Guanabara

Bay, it could soon be dangerous to swim in a sea filled

with toxic plastic waste. Ocean ally, Bluebird

Marine Systems is pioneering eco robots

that can vacuum up plastic waste and offload while at sea, by

coupling with a converted bulk carrier called a PlastiMax.

MANILA

BAY -Manila Bay is a natural harbour which serves the Port of Manila (on Luzon), in the Philippines. Strategically located around the capital city of the Philippines, Manila Bay facilitated commerce and trade between the Philippines and its neighbouring countries, becoming the gateway for socio-economic development even prior to Spanish occupation. Manila Bay drains approximately 17,000 km2 (6,563.7 sq mi) of watershed area, with the Pampanga River contributing about 49% of the freshwater influx.

As you can see from the picture above, the bay is awash with

plastic and other garbage.

In 1997, polychlorinated biphenyl congeners (PCBs), compounds common in transformers, hydraulic fluids, paint additives and pesticides were determined in sediments and oysters sampled from Manila Bay. The increase in the nutrient concentration and presence of nitrate, ammonia and phosphate in the

bay from the '80s, through to the '90s and beyond are not only attributed to agricultural runoff and river discharges but also on fertilizers from fishponds.

Plastic soaks up PCBs, passing that poison onto whales and

dolphins.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

http://www.theguardian.com/profile/lindsey-kratochwill

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/mar/26/ocean-cleanup-project-environment-pollution-boyan-slat

http://www.independent.co.uk/environment/nature/how-scientists-plan-to-clean-up-the-plastic-waste-threatening-marine-life-a6820276.html

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/uk-whales-and-dolphins-at-risk-of-extinction-due-to-lingering-toxic-chemicals-a6812171.html

http://www.independent.co.uk/environment/nature/almost-every-seabird-will-have-eaten-plastic-by-2050-because-of-ocean-pollution-10480117.html

http://www.independent.co.uk/author/steve-connor

|